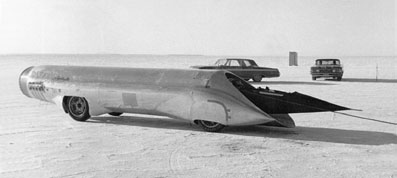

The Infinity jet car

Glenn Leasher's Infinity,

before the fatal run

(photo Ron Christensen)

By the late fifties surplus jet engines from the US Air Force and Navy became available, for fairly reasonable prices, to anyone with a good use for them. Racers could not dream for a better, and cheaper, source of seemingly unlimited power. The drag strip and the Salt Flats looked like the most obvious place to take advantage of the new power source and as early as 1960 the first jet dragster (Walt Arfons' Green Monster 16) and the first jet land speed record vehicle (Dr. Nathan Ostich's Flying Caduceus) had made their appearance. It was the beginning of a new era.

In a matter of months new jet vehicles were being designed and built all over the place and in August 1962 the SCTA Speed Trials witnessed a unique collection of no less than five jet vehicles, four of them brand new.

None was very successful that year, although a couple of the wild youngsters behind those projects were soon to mark the history of the LSR in one of its most exciting moments: Craig Breedlove went back to the drawing board to correct the many teething problems shown by his Spirit of America, while Art Arfons did set the first (and only) record in the newly introduced SCTA jet car category(*) at 330+ mph, but realized that Cyclops, his unstreamlined jet car, was good enough for the drag strip but not for the LSR, where 400 mph was the target, and he too decided to go back home and build a new car around a more powerful engine... A third contender, Bill Frederick, although he could not run his Valkyrie on the salt (it eventually became a drag strip attraction), was to have his niche in the history of the LSR, albeit controversial, a few years later, with his rocket vehicles. As to Ostich, who had returned with his Caduceus, he would be back once more in 1963, before he realized that a slower but safer life was better for him...

Infinity in the workshop, Leasher at the helm

(photo clipped from unknown german magazine)

Not many people remember much about the fifth jet car, its builder or its driver. Built by Romeo Palamides and driven by Glenn Leasher, Infinity was indeed, in my humble opinion, the only one in the lot to possess at least a hint of that special quality we, italians, consider so important in a car, beauty. True, Spirit of America was indeed a beautiful car, but in fact beauty came to it only a year later, when the fin was added and some other details modified: in 1962 it was an ugly duckling just like the other three.

Problem is, Infinity's career was all too short and quickly ended in tragedy: people were more than happy to forget about it. An easy task, considering that, unlike its rivals, this car had very little coverage in the press while under construction, and then again very little when it first appeared on the salt on the last day of Speed Week, only to return quickly to the workshop after just one test run that had revealed some chassis problems. When it came back to the salt in September, in just two days its fate was written.

Problem is, Infinity's career was all too short and quickly ended in tragedy: people were more than happy to forget about it. An easy task, considering that, unlike its rivals, this car had very little coverage in the press while under construction, and then again very little when it first appeared on the salt on the last day of Speed Week, only to return quickly to the workshop after just one test run that had revealed some chassis problems. When it came back to the salt in September, in just two days its fate was written.

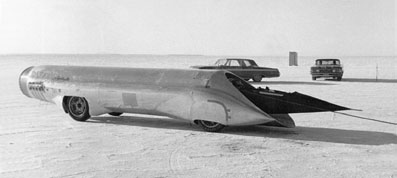

(Above and left) Speed Week 1962, Infinity arrives the last day (photos from Peter Holthusen's "The Fastest Men on Earth")

Cyril Posthumus' book "Land Speed Record", which is still considered the bible of LSR fans and scholars, did not even mention it, although it dealt with more obscure projects that did not even make it to the build stage (the gap was later duly filled by reviser David Tremayne in the second edition of the book).

As a matter of fact, it has been quite a task to put together enough photos and information to produce a reasonably accurate model, since no more than a dozen photos of it have been published over the years, of which half are of the wreck after the fatal accident...

Infinity getting ready for the first test run in August

(photo from Motor Trend magazine)

And yet, in retrospect, Infinity did probably have the potential to achieve its goal, and all the "faults" in its design that have been indicated as the likely cause for the accident cannot really be considered crucial, as experience with other vehicles before and after have shown: the driving position, forward of the front axle, may not be ideal to sense the behaviour of the vehicle, but did not cause any special problem to John Cobb with his Railton or to Bobby Tatroe on the Wingfoot Express rocket, or to Art Arfons on either Anteater or Cyclops, or to any of the jet dragsters that shared the same driver's position. It was a weak position in case of an accident, that is sure, but then again, this was never given any special attention when dealing with any of the other cars I mentioned. So much so that Craig Breedlove adopted it again in his most recent Spirit of America.

Infinity did not have a fin, and a fin could have helped, according to many opinions, but again, we have seen cars without a fin succeed and cars with a fin crash, so again, it might not have been a crucial factor. Railton did not have a fin, nor Mickey Thompson's Challenger and they were both safe and reliable cars. Besides, had things gone in a normal way, the team might have come to decide to add one eventually, like many others did, Breedlove and Donald Campbell heading the line.

Infinity being hauled to the salt

(photo from Fred Kaesmann's "Weltrekordfahrzeuge")

As to the building quality, Romeo Palamides was no newcomer, he had built dragsters in his Oakland , CA workshop for quite a while, including The Untouchable, a jet dragster that was a close sister to Infinity, if not a twin, minus the body shell. And it was a relatively safe and successful car in the hands of Glenn Leasher himself and later of Bob Smith. (Incidentally, Palamides would later build rocket dragsters as well).

Infinity had a spaceframe very similar to The Untouchable, but used a more powerful J47 with afterburner (actually a fresh engine, not a worn out one) and, even if the front axle was from a Ford, it provided efficient steering, unlike most other jet vehicles. The aluminum body (which was never painted) was designed by Vic Elisher, and had been built by a firm in Berkeley.

As a matter of fact, in the mere three runs Infinity had done before the fatal one, it had been clocked at 330 mph: it was no bluff at all.

Leasher and the crew fitting the chutes before a run

(photo Ron Christensen)

Apparently what really turned a promising project into tragedy was impatience, most likely from the part of the driver himself. Glenn Leasher was a young, but experienced drag racer and that might have been the point, that he was a drag racer. Witnesses say that in that last run, on September 10, he accelerated too much too quick, then something broke, or the car just lost balance, because of the brutal acceleration. Leasher was just after the first mile and already travelling, according to witnesses, at over 250 mph when the car yawed to the left and in a matter of seconds it was flipping and rolling; then it caught fire and Leasher stood no chance, although he had probably been killed when the nose of the car had hit the salt almost vertically (the run was to be officially timed, so film crews were present, the accident was filmed and you can find the sequence in commercially available videos).

Besides his drag strip driving style, why exacly Leasher should have felt it necessary to go out for the record all too quick is not clear. Jet vehicles were something almost totally new and his one in particular was brand new. A wise attitude would have been to build up speeds gradually over a good number of test runs, to check and correct flaws and problems and get used to the behaviour of the car.

Reports tell us that he had just been secretly married to his sweetheart and they planned to reveal it publicly as soon as he would get the record. Others add that he had just been given the news that his wife was pregnant. And then, you have that key factor, always hanging over the head of a LSR challenger, the time/money factor.

Whatever the reason, he paid the highest price for his impatience.

A close up of the front

(photo Ron Christensen)

A NOTE ON BODY CHANGES AND MODEL DETAILS

Between Infinity's first appearance at Speed Week in August, to which most of the photos you will find in books or contemparary magazines refer, and the September record attempt, the body had been slighly modified: the front wheel fairings had been extended towards the back by adding a new triangular panel and the jet aperture in the tail was now surrounded by a ring of metal with a rim all round, likely to avoid the airstream outside the car to mix with the air ejected through the engine, thus possibly reducing the thrust, or maybe to help directional stability.

One puzzling detail, in trying to produce an accurate model, concerned the chute compartments: they had metal panels flush with the body lines in August, but these covers are never in place in any of the September photos, or in the video footage: the parachute bags are exposed and strings from the chutes appear to be scotch-taped to the body. Wether this was the definitive solution, or a temporary one during tests is not clear. They were like that during the fatal run, as the bags were rescued still unopened after the crash, and this was a timed run, potentially a record run, so the doubt stands. Whatever, none of the photos available to us allowed for an accurate reproduction of this detail so we decided to release the model with the metal covers in place:after all, it had certainly been originally planned to run the car that way.

As to the rear wheel covers, as featured on the model, although they do not appear in place in any of the photos, they were actually on the car during the runs: they can be clearly seen in the film footage and, more importantly, I have seen photos of remains of one of the rear wheel arches that still have parts of the covers attached to them. These same photos allowed accurate reproduction of all the decals and lettering.

NOTES.

(*) The jet category had been introduced that year, given the number of racers that were willing to run jet vehicles, but insurance problems arose and only Arfons did actually run officially in the Trials, eventually setting an official SCTA record, after arranging his own insurance. None of the other cars ran, although they did private test runs either on the salt or on the runway at the airfield. The same insurance problems made the SCTA decide to ban jet cars for the next Speed Trials (to the SCTA credit, the 1963 program states "unfortunately") and jet cars have run on private sessions ever since.

The remains of Infinity stood for many years at Wendover, as a memento that land speed records are indeed a dangerous game (photo Ron Christensen)

Special thanks to Ron Christensen for supplying some previously unpublished photos that truly made an accurate model possible at last (some are published here for the first time), and to Don Baumea for his advice and support. Information used in the text also comes from Posthumus & Tremayne's "Land Speed Record" and from contemporary magazine articles. Photo sources are duly acknowledged, and photos are reproduced at low resolution for reference only. You should check the original publications for full quality images.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Home

| About Ugo Fadini | Current models | How to order | Discontinued models | Models to come | Articles & Stories | Links

© Ugo Fadini 2000/2005 - page last updated 22 June 2003

Problem is, Infinity's career was all too short and quickly ended in tragedy: people were more than happy to forget about it. An easy task, considering that, unlike its rivals, this car had very little coverage in the press while under construction, and then again very little when it first appeared on the salt on the last day of Speed Week, only to return quickly to the workshop after just one test run that had revealed some chassis problems. When it came back to the salt in September, in just two days its fate was written.

Problem is, Infinity's career was all too short and quickly ended in tragedy: people were more than happy to forget about it. An easy task, considering that, unlike its rivals, this car had very little coverage in the press while under construction, and then again very little when it first appeared on the salt on the last day of Speed Week, only to return quickly to the workshop after just one test run that had revealed some chassis problems. When it came back to the salt in September, in just two days its fate was written.